You’ve held them countless times without pause. Quarters passed across counters, dimes dropped into parking meters, coins turned in the air during moments of indecision. They move through our hands almost unconsciously. Yet if you slow down and run your thumb along the edge of a coin, you’ll feel something deliberate—tiny grooves cut with care. They aren’t decorative, and they aren’t accidental. They are a remnant of a time when money itself was fragile, and trust could be eroded a shaving at a time.

Three centuries ago, coins were struck from real silver and gold. That value invited abuse. The crime was called coin clipping. Thieves would shave small amounts of precious metal from the edges of coins, saving the slivers to melt down later. Each altered coin still passed at full value. Individually, the loss was almost invisible. Collected across thousands of coins, it became a quiet form of economic sabotage. Governments lost metal, merchants lost confidence, and entire monetary systems weakened under suspicion.

The problem grew serious enough to threaten national stability, forcing authorities to respond not with punishment alone, but with design.

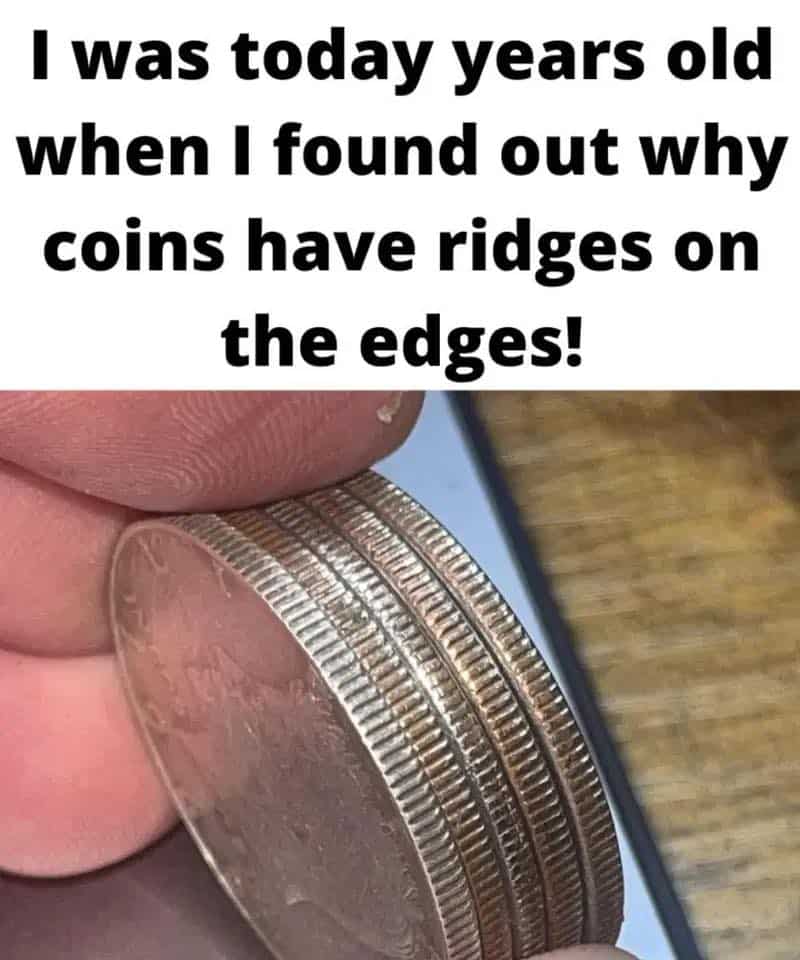

In 1696, Isaac Newton—already renowned for his work in mathematics and physics—was appointed Warden of the Royal Mint in England. He approached the crisis methodically. His solution was simple, physical, and difficult to circumvent: reeded edges. The evenly spaced grooves pressed into the sides of coins made tampering immediately visible. A clipped coin would show broken or uneven ridges; a legitimate one would not. At the time, counterfeiters lacked the precision to replicate the exact spacing and depth of the mint’s work.

The change worked. Coin clipping became easier to detect and harder to deny. Newton went further, personally overseeing investigations that dismantled counterfeiting operations. It was an early example of anti-fraud technology—not loud or punitive, but quietly effective. The integrity of currency improved because honesty was built into the object itself.

Today, most coins are no longer made of precious metals, yet the ridges remain. They still serve practical purposes. Modern machines use edge patterns to help identify legitimate coins. For people who are blind or visually impaired, the texture allows different denominations to be distinguished by touch alone. And there is continuity in it, too. Ridged coins feel familiar, sound distinct when they meet, and carry forward a design language shaped by necessity rather than ornament.

Pennies and nickels remain smooth for a reason. They were never made from valuable metals, so there was little incentive to tamper with them. Their simplicity reflects a different risk profile, not an oversight.

Those small grooves circling your coins are more than a habit of design. They are evidence of a lesson learned long ago: that trust is preserved not by assumption, but by structure. Sometimes the most enduring safeguards are the ones we barely notice—quiet measures that hold firm precisely because they don’t demand attention.